Trump’s latest gambit over Greenland sounds absurd until you remember where your data lives.

The US president floated tariffs against its allies (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Finland) if Denmark won’t discuss selling Greenland to the United States. The proposal itself is unlikely to succeed, but what it reveals about the current geopolitical climate matters for organizations running critical infrastructure on American platforms.

For European organizations running critical operations through Microsoft 365 or Google Workspace, this should feel uncomfortably familiar. Your collaboration infrastructure, your institutional memory, and your daily operations all sit on servers ultimately subject to US jurisdiction. Not just US law, which is predictable enough, but US political pressure applied in directions you can’t anticipate.

The pattern we keep ignoring

We’ve seen this pattern before. The Privacy Shield framework collapsed when courts recognized that US intelligence access to European data wasn’t theoretical. CLOUD Act provisions give US authorities reach into data stored anywhere in the world if a US company controls it. These weren’t bugs in the system. They were features that only became problems when someone decided to use them.

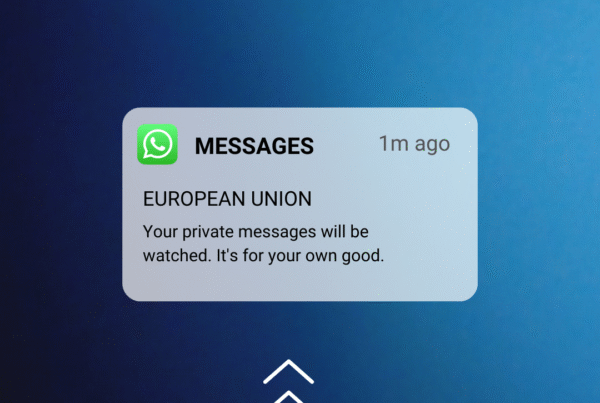

Digital sovereignty used to sound like bureaucratic anxiety dressed up as policy. Something for compliance officers to worry about while the rest of us got work done on platforms that actually functioned well. But sovereignty is just another word for control over things that matter. When political winds shift, and your communications infrastructure becomes subject to leverage you didn’t agree to, “where does our data actually live” stops being an abstract question.

Beyond compliance theater

The shift is already visible. Government ministries are moving to domestic providers like Nextcloud. Organizations are reconsidering their cloud strategies. Not because American platforms work poorly, but because the ground underneath them keeps moving in ways that have nothing to do with technology.

This is where the conversation about European alternatives changes character. Solutions that connect Outlook and Teams to infrastructure like Nextcloud give organizations actual choices about where their data lives. These tools weren’t built because European developers couldn’t figure out how to make a decent cloud platform. They exist because operational continuity shouldn’t depend on the stability of transatlantic relations.

Organizations gain the freedom to choose their infrastructure strategy without abandoning the collaboration tools their teams already know. They can migrate entirely to sovereign infrastructure when that makes sense. They can adopt hybrid approaches that protect sensitive data while keeping other workloads on platforms optimized for public-facing services. They can make these decisions based on their actual security requirements rather than accepting whatever terms their current vendor offers.

The ability to safely migrate to sovereign infrastructure or use a hybrid approach transforms infrastructure decisions from locked-in commitments into strategic choices you can revisit as circumstances change. That calculation looks different now than it did five years ago. Probably looks different than it will five years from now.

The technical part is easy

Microsoft’s protocols are well-documented. Exchange can sync to other systems. Teams can coexist with platforms that keep data inside EU borders. The harder question is strategic: at what point does convenience become dependency, and dependency become vulnerability?

We’re willing to wager that Greenland isn’t going to become US territory. But the threat was real enough to make. That’s the point. When essential infrastructure sits under someone else’s ultimate authority, you’re always one policy shift away from discovering that what you thought was a technology decision was actually a geopolitical one.

Who controls the off switch

European organizations are waking up to this in different ways and at different speeds. Some are moving deliberately to platforms they control. Others are building hybrid approaches that keep sensitive operations on domestic infrastructure while using US platforms for less critical work. The common thread is recognizing that where your data lives isn’t just about latency or compliance checkboxes.

It’s about whether you’re comfortable with someone else holding the off switch.